Letter 2:

Academics:

Proving Myriads Wrong

Dear Reader,

Nearly every single letter writer explored how Hampshire was different from their previous educational experiences. In this letter we will explore the most prominent patterns I found.

In her letter, Madi Chassin, who graduated in 2019, and now works as a production assistant for television shows, reminisces about her high school days with her younger self. She writes:

“Remember in high school you did fine, grade-wise. Not great, not terrible. Maybe terrible in math and science, maybe great in history and English. Overall, average. You liked history and English, you actually almost enjoyed those classes. Almost. In reality, you were too stressed out to enjoy any of it. Due to the stress and stress alone, school sucked. I’m excited for you to learn that at Hampshire all of this changes. Hampshire makes you realize that you love learning. I guess in a way you always loved learning, but that was bogged down by the frustration of sitting down in front of a science test and feeling like a complete idiot. You knew you were smart, but that system had a way of making you feel so dumb. At Hampshire, you get to just learn. You are learning for a living. A year and a half out of Hampshire and I wish that I was in your position where my whole job was just to learn. It turns out that school never has to suck again.”

I see myself in her words. I recognize the pattern that I use to push myself within Chassin’s words. The pattern of not exactly feeling dumb but not exactly feeling smart. A Newton’s cradle of energy that would swing me to either side of this belief. It was the system that kept the momentum going. It was the system that told me that even though I harbored an extreme love for English studies, I was fascinated by the dissection of themes and metaphors and that I would be willing to write until my hand fell off, and pick up the pen with the other when it did, that my work and effort were not strong enough.

Whenever I asked to advance to the next level, I always got a myriad of “not quite,” A myriad of “almosts,” of “so close but…” “if you just tried a little harder you could…”

A myriad of Nos

“No,

because you make too many spelling mistakes”

“No,

because you put your commas in the wrong place”

“No,

because you pronounce too many words wrong when you read out loud”

“No

because your handwriting is horrendous, and I can barely read it so how do you expect the honor teachers too?”

“No,

because you don’t read as fast as the other kids”

“No,

because you do not think in the lateral ways that those teachers would want you to”

“No,

You go off the syllabus too much, They’re not going to let you be so loose with the curriculum And do these “alternative projects” as I do”

Ha!

“Do you honestly believe

you could keep up?”

because sprawled in big letters in my educational file was dyslexia. A flashing warning sign to not let me go past a certain point. It took me till the end of my sophomore year of high school to convince a teacher that my work was good enough, that inadvertently

I was good enough.

And even after all that work, when my junior year rolled around they almost didn’t let me take the course because I asked to keep my accommodations.

After reading these letters, It became extremely clear to me that Chassin and I were not the only ones who battled with the education system.

Obedience and subjectivity

A person who has a lot of insight into the American education system is Casey Zella Andrews. Andrews has a lot of experience working both in the classroom as a learner and as an educator. Andrews is a Hampshire College graduate of 2012. After Hampshire, she received a Master of Arts in Teaching from Simmons College and an MA in Critical and Creative Thinking from the University of Massachusetts Boston. Andrews has been teaching high school English for the past seven years; prior to that, she worked as an elementary school teacher in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

When I got the chance to sit down and talk to Andrews about her letter, she expressed her views and experiences working for and in the American public school system. A topic that struck me was her explanation of a student being “good enough” for the education system. Andrew says, “our school system is set up with a lot of binary and linear systems… some things are good, and some things are bad. If you are doing good, it’s measurable quantitatively..schools really determine, “this is what a good student looks like.” And it’s based on a lot of cultural things about what goodness is. And then if you’re not adhering to that, and if I’m in a position of power, whether it’s teacher, Principal, Dean of discipline, etc, I’m allowed to penalize you in whatever way I personally feel like I want to do whether that’s not letting you advance whether it’s giving you an F, it’s telling you, you can’t play your sport. And I’m entitled to that because you’re not being good enough. And I think that is in lots of different interactions.”

As we speak, Andrews explains this concept more with her own personal antidotes, which ring very true to my own. She told me, “in ninth grade a teacher said, “You know, I would move Casey in 10th grade to the honors class or the advanced class, but she just doesn’t put enough effort. So I’m not going to do it” and refuse to put me in the advanced class. And that really tainted my educational experience… to have a teacher say, you’re not putting in the amount of effort I would personally like to see. And therefore even though I can see that you’re capable of doing this work, you’re not allowed to go do it. And… in 10th grade my English teacher accused me of plagiarizing an essay because I had an idea that we hadn’t talked about in class … I had done the same book in eighth grade. So it’s an idea that I had discussed and talked about in my eighth-grade English classes. I wasn’t plagiarizing from a place, it was an idea I had learned and then carried out with the book…These two teachers were trying to uphold the integrity of the system as if like, you know, me going to the advanced class without quote, putting in the right amount of effort for this teacher or me having this idea, even though we hadn’t talked about it, these went against what the system was looking for, which was… a kind of blind, passionate obedience, and dedication to work.”

Andrews’s and my experience align in the fact that both of our efforts were not seen as “good enough” by the current public education system. The system’s subjective perspectives somehow decide that a student’s effort is too minimal. It is a system that punishes those whose understanding of information diverges too much from the course material. The approaches that we took to our education were not viewed as adequate because they did not showcase a willingness to obey the status quo.

Andrews went on further in the conversation to say that disrupting the prior model of a “good enough student” was still something she was combating as an educator. She tells me a story of a current interaction she had with another teacher. “This teacher emailed us, the 12th-grade teachers of this particular student, saying that she didn’t want us to, quote, reward a student who wasn’t putting in the effort, because the student is failing their classes, but they want her to be able to play a sport. The teacher’s email is riddled with this language about how she understands how hard it is to reward a student who might not be working hard… but like we’re in the middle of a pandemic, but also, in general, I don’t want to wield rewards that students have to buy or earned from me with their work ethic, like that just doesn’t really seem like the model of education that we should have.”

From the experiences Chassin, Andrews, and I share, it is clear that the current American public education system runs on a biased format. What a student deserves or doesn’t deserve is not determined by the individual effort and growth that the student displays. Instead, the actual potential for opportunities, be it a good grade, the capability to take on more challenging work, or playing a sport, is determined by those who help run and manage the system.

It’s not just early education...

Andrews explained that this system built on subjectiveness and obedience is not only found at an early education level but says that “A lot of colleges are set up to continue building that narrative.” Other letter writers seemed to agree with her.

Shelly Johnson Carey, a graduate of 1979, Masters in Fine Arts holder, and writer of “New Horizons” an alternative to Seventeen Magazine for Black Teens, and the book “Thin Mint Memories: Scouting for Empowerment through the Girl Scout Cookie Program” told herself about the differences that she saw between Howard, a school she attended for a couple of semesters and Hampshire. She writes to her younger self that “At Howard, you learned whatever the professor told you would be on the test. And you did well! But, how much of that information do you still recall? In Hampshire courses, you will delve into readings and discussions that will engage you, challenge you, and sometimes infuriate you. However, as you connect your knowledge, you will find that—along with the growth of your own knowledge base—you’re learning how to ask the right questions and sort through ideas to draw your own conclusions. And by creating your major in Div II and designing your senior project in Div III, you’ll learn how to see each twig and leaf make up the trees and, ultimately, the forest. Once you’ve completed your Hampshire studies, you’ll be able to plan and manage large and small projects…that ability to imagine, plan, and execute a project will allow you to be successful.”

In this passage, Carey explains to her younger self that colleges can mirror early education, relying on obedience that is often instilled in learners before they reach higher education.

The difference in systems that education institutions can operate under can still be seen in current times. In her letter to her younger self, Nora Hammen, a Div III graduating this year (2021) and working on the 5th draft of her novel “The Witch University,” writes a similar message about the difference she sees in the education styles of different colleges. She writes to herself “There [Reed College], the classes excite you because they are college classes, already miles different and better than those you took in high school. Here [ Hampshire college] the classes excite you because they go more in-depth, have more student involvement, and allow you to explore outside what you originally think you’re interested in. There, the structure is very stereotypically college-like, with rigorous classes and intense finals periods. Here, the structure is self-driven and better fit to your needs, with classes that intrigue you and finals that build on what you learned rather than testing you on it. Hell, eventually you’ll take Hampshire’s unique system for granted so much that taking classes at the other five colleges throws you off because what? We have to take a TeSt? And there are GrAdEs???”

Both Carey and Hammen expressed how higher education can carry the same expectation for obedience as early education does. They also described how Hampshire differed from their prior experiences. Other letter writers followed this pattern and wrote about how vast a contrast their Hampshire experience was from their previous schooling. When writers wrote about the educational experience of Hampshire, their commentary mostly fell into one of two categories.

The Hampshire difference

- Professors that care

This section is not to say that educators at other academic facilities do not care about their students. If there is going to be a true and healthy educational exchange of any kind, there has to be some level of care on both ends. I believe there are many outstanding educators who are genuinely invested in the wellbeing of their students, both on an educational and emotional level, many of them being my own teachers of the past. However, a difference in how Hampshire professors approached teaching students and how educators at other facilities do was a pattern that I noticed in peoples’ letters.

Andrews summed up professors at Hampshire as we discussed her undergraduate experience. She says a big difference that she noticed between her teachers in early education and her professors at Hampshire was that her professors “just wanted me to learn. And I felt like that was really reinforced in my personal interactions with them…Teachers meeting with me and like really wanting to hear my ideas, really interested in what I had to say, really trying to find me the best article that I could read to expand my thinking about something.” for example, in “Lynn Miller’s class, my natural science requirement my freshman year. I hated science, mostly because of terrible experiences in science classes… The class was genetics, and he required you to meet with him to pass the class. I did terribly on my papers. I had no idea how to write about science. But he walked me through every single aspect of what I was doing terribly in my paper. And I learned so much in his class. I don’t know a lot about genetics, but I know much more than I know about almost any other science topic. I think it wasn’t because I was even more interested in learning about genetics during that semester, but it was because I could feel that this person was working in relationship with me in this open and supportive way to make sure that I learned as much as I could. And I just really never had that quality of interaction with most of my high school or middle school or elementary school teachers. Which is sad. And I think now as a teacher is like what I’m working against, but it’s hard within the confines of the institutions and systems that are surrounding education.”

The type of connections students form with their professors has been a well-established tradition since the college’s foundation. Leslie Hiebert, a 1978 graduate who went on to be a public defender in Alaska, tells her younger self the tale of the professor who helps set her on this path. She writes, “The best help was a conversation with a stunningly empathetic professor, in a field never yet considered, the gentle balm of ethics, integrity, civility. Sorting out some of the key questions was a monumental task, in the end, all the schools helped frame and build a platform of understanding from which you could drive ahead. You left Hampshire feeling you had little cohesion around a “major,” a grab bag of ideas, explorations, interests, but appreciation for Lifelong Learning tools.”

Naomi Wallace, a Div III in 1982 and now an award-winning playwright, enlightens her younger self with a similar message. “Andrews Salkey is one of your teachers. He is the most inspiring teacher you have ever met. You go to his office and you talk about Cuba and revolution and language and how words can change the way we think and feel. You have coffee together in his office. From his window you see trees. Andrews says, “Poetry matters,” and he tells you it is labor. Andrews takes your writing seriously. He tells you that you can become an important writer if you practice and work hard with words.”

Hampshire is not the only learning place in the universe with educators that are genuinely invested in the academic paths of their students. However, the unique connections that students have been able to form with faculty and staff here at the college do strike as different from many students’ prior experience with educators. The amount of care, consideration, and trust that professors put into their students to explore and do the work help make the Hampshire experience very different from other educational routes.

2. Change in the way we view effort

As noted above, a significant issue that appears for students participating in other academic institutions is that there seems to be a very constricted lens through which knowledge can be viewed and through which students can work. . Many letter writers expressed that Hampshire was a space that they could break free from this prior academic confinement.

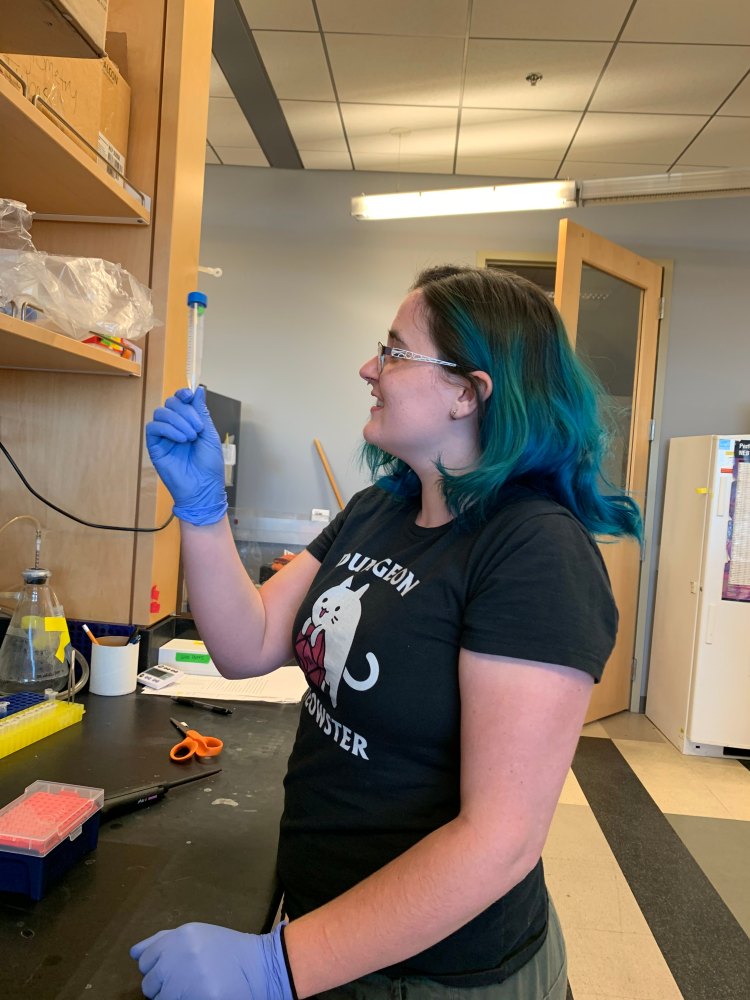

Isabelle (Issy ) Tobey, a 2018 graduate and current Ph.D. student studying cancer biology at the University of Arizona in Tucson, sums up the academic freedom that Hampshire provides beautifully in her letter to her Div I self. In the letter, she writes, “[Hampshire College] is very much a find-your-own-path, make-your-own-way kind of school. And, at this point, you know you thrive when you can just chase your bliss.”

Students who have attended Hampshire throughout its generations of operations expressed similar sentiments.

Ellen Sturgis, a 1980s graduate and now an admin for the Hampshire college’s Alumni Advisory Group, Hampshire college’s board of Trustees, and the Selectboard of her hometown, wrote in her letter to her younger self about the experience of being able to mix and match the lenses she learned through. She writes to her younger self that “the lines were blurred, I applied history to Language & Communications for a Div I in an analysis of how leading newspapers covered the same event very differently. My takeaway, looking back, as to the value of this being a liberal arts college is that I learned, via the Div process, how different disciplines analyze “data.” And that is what is possibly the biggest lesson I hold today. I learned to think critically and see a problem from different angles.”

Kelly Anderle, a 2011 graduate, who after graduation, moved to New York City to work for legal advocacy and tenant rights before going back to get her school counseling degree, explained her gratefulness for the academic freedom Hampshire granted her. In her letter, she writes, “Then there’s the slide for the Hampshire classes, for the intellectual growth, for the freedom to think and learn and follow my brain for four years straight without constraints of grades and requirements. Total luxury. To dance between five colleges as I pleased, to drive all around New England for fieldwork, to use the turns of phrases I so rarely use anymore: critical ethnography, literary journalism, reflexivity. My deep listening germinated at Hampshire. My courage to go into unknown places took root.”

The academic freedom and trust Hampshire puts in its students to guide their own learning allows them to engage in their education in ways that many weren’t able to do prior.

To the future

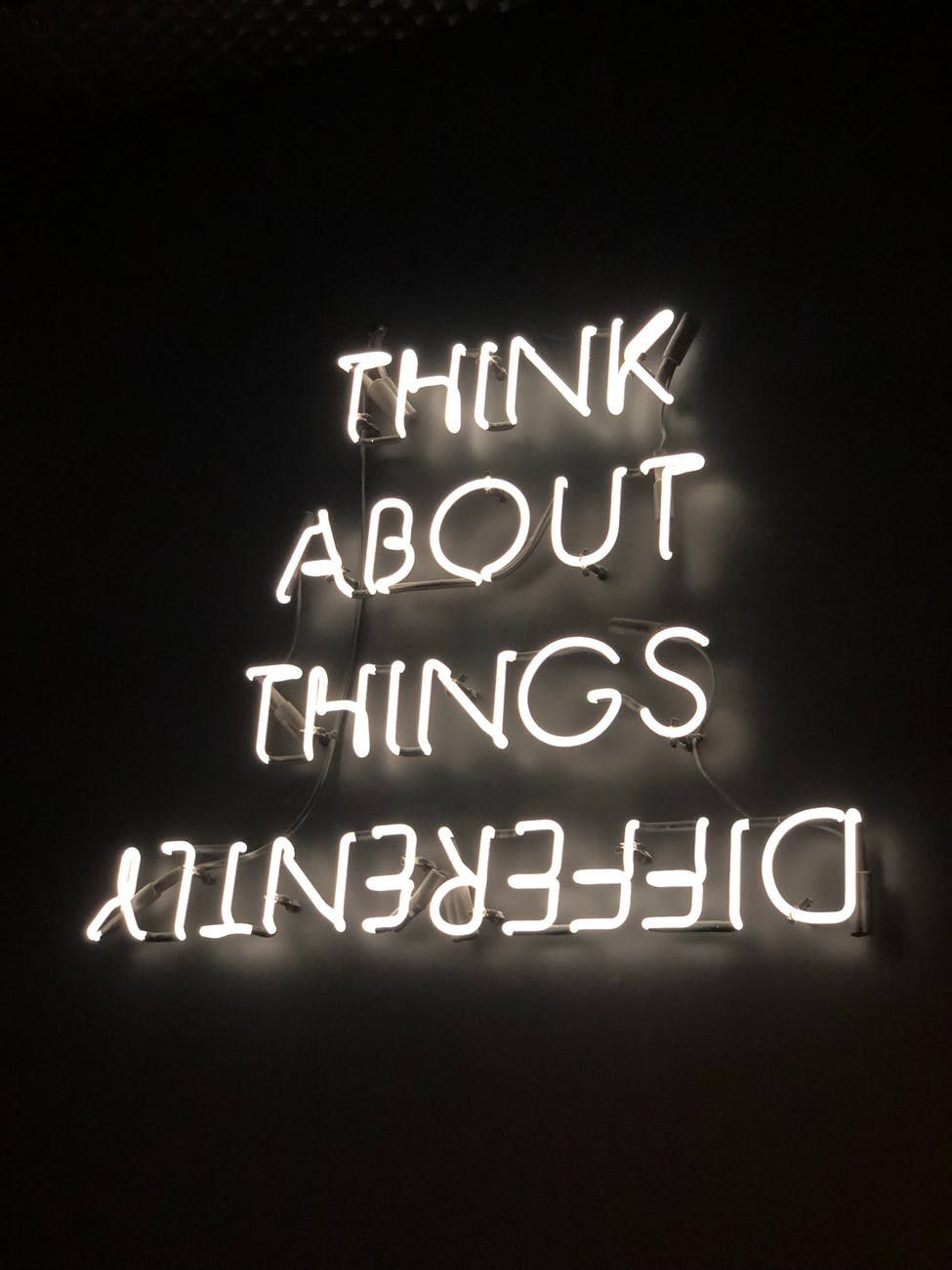

At the end of our conversation, I asked Casey Andrews to name the most important thing she wanted her students to know?

This is how she answered.

“what I hope for them is that they find those kinds of authentic, opening experiences that allow them to keep learning or keep changing the way they think about things and see things. And when I see those moments in my class, even right now, like when they’re able to be like, Oh, my God, I never thought about it that way. Those moments cumulatively are what impact us to change the course of our lives. And I think Hampshire did that. For me. I think it does it for a lot of people. And I hope for my students that they’re able to find those opportunities, you know, wherever they end up going.”

And I think right there is truly how Hampshire students make it work after graduation. What helps us make it work is our openness to experiences that allow us to keep learning and keep changing the way we think about things and see things. When we approach the world from a flexible angle, our pursuit of knowledge goes beyond knowledge itself, and in doing so, we can grow, explore, and change for the better.

Non-Satis Scire

That’s the Hampshire way.

Reader, What is your way?

Sincerely

Molly Marie

Featured in this letter

Div III 2019

Div III 2012

Div III 1979

Div III 2021

Div III 1978

Div III 1982

Div III 2018

Div III 1980

Div III 2011