Letter 3:

Creataors:

You don’t have to be starving to be an artist

Dear Reader,

This is not what I originally came to college to do. I did not come to college to write letters, connect with others through writing, reading, sound, and film, no this is not what I came to do. I came to college to learn to be an educator or a psychologist or something along those lines, something practical, something I viewed as guaranteed to get me a job. The pursuit of higher education was always presented to me as a tool, an aid to advance to the next stage of my career. The pursuit of higher education was not supposed to be an exploration or a place for creative experimentation, not a breeding ground for curiosity. Then I met Hampshire. Then I met Hampshire’s philosophy; then, I met how students questioned what students created. Most importantly, I met Dog.

Dog walked into my life very early on in my college career. I mean this in the most literal way. On the first day of orientation, not even an hour after my parents had left me, Dog barged into my dorm room, stuck out her hand, and loudly proclaimed a greeting and her position as my hallmate. Next came a semester full of blurred events: a series of wrong buses taken to surprising right locations; becoming stranded in a mini atm bank after a movie about a killer clown we thought was over at ten actually got over at midnight; multiple loops on rollerblades around campus, and late nights staying up listening to Cherry Wine and talking about everything and nothing all at once. Before I knew it, the weirdo that barged into my room on the first day of not even school but orientation had become one of my closest friends at the school. And now, almost four years later, She is one of my best friends PERIOD.

Dog is one of the most adventurous souls I have ever met. She is always open to new experiences, new challenges, new ways of doing things. I believe it is fair to say that she is not only open to these things, but she actively seeks them out and has a way of radiating this “try anything once” energy to the people around her. Or, at the very least, she radiated it off to me.

In the second semester of our friendship, Dog convinced me to take a film class with her. I was hesitant at first, even more hesitant once I learned it was an advanced level class. and actually became a little frightened when I met the professor and saw how much she expected from us

Though challenging, even chilling at times, this class made me fall in love with the idea of being an artist. I fell in love with analyzing the visual. Over and over again, in previous courses, my eyes had scanned through text, finding meaning and patterns, themes, and metaphors; in art, analytics came with more layers. There were not just the words, but there was color, there was contrast, there were camera angles and body language. It was like discovering stories within stories, a whole universe of new ways to construct and communicate meaning. I fell in love with the process. It is one thing to sit down and write an essay; it is another to put the essay on the screen. I fell in love with going out to find locations that served as good backdrops to the stories I wanted to tell. I fell in love with going hunting for sound bits, of playing with materials to make one thing sound like another, I fell in love with filming and re-filming to get the “perfect shot”, I even fell in love with the tedious and partly torturing editing challenges that premiere presents. In this class, I decided that I would defy all my prior notions of higher education and make it work. The life the work breathed into me was worth the risk of it taking the breath out of me.

As school went forward, I dove deeper. I took courses that taught me how to tell non-fiction stories with the flair of fiction. I learned in other classes that the best documentary stories zoom in on the smaller pieces then zoom out to show you the whole picture. I did projects that caused me to practice finding every detail, describing them in-depth, yet not too in-depth, that you lose the true meaning of the composition. I dove deeper into listening, into pattern finding, into crafting visuals and text, I dove deeper into the art of storytelling.

However, as I worked, so did reality. The world after Hampshire inched closer and closer. As I’ve worked on this project, reality has been standing at my doorstep waiting for my diploma to be handed to me. Waiting for this moment to open the door and make me come face to face with them.

I do not fully know what reality will look like; however, I’ve pictured my old beliefs that I had been raised on filling the frame.

Though I have put myself in an artist world as an adult, I was born to a monarchy of realists. I was born in a place that has trained me since I was young to fit in, to live up to a society’s version of perfection, and though all through college I have worked on unlearning to lean into these cautions, there is still a piece of me that finds support in them.

With this picture came doubt. Doubt about if I had made the right choice; doubt about my education; doubt about my future, doubt about everything. Then I read the letters of those who came before me and of those who stand in the same spot as I do now. Creators just like me who faced a waiting reality. The letters that they wrote describe how they did it and how they continue to do it, how they live the life of an artist without starving.

- Community

It is often said, “it takes a village” to raise people up. It takes a village to raise a child to be a productive member of the community; it takes a village to re-build structures that have crumbled. It takes a village to help those out of the rut that people can fall in. As seen in the letters, The phrase “it takes a village” rings true for those who subscribe to an artistic life.

As a graduate of 1977, Ellie Siegel was a part of some of the first cohorts of students who completed the Division III process and later came back to teach at Hampshire. In her letter, she writes advice to every year that she had spent at Hampshire. To her second-year self, Siegel notes the importance of the people who surround her and how they influence her own creative process. She tells herself that “You are having some interesting conversations with the other artists in your mod, who include painters, musicians, and a filmmaker. You’ve never realized before how making things and doing creative work involves asking similar questions and attending to similar concerns, no matter the medium.”

Naomi Wallace, a Div III during 1980 and now an award-winning playwright, enlightened her younger self with a similar message. Wallace tells her younger self in her letter that “You learn you love theater more than writing poetry because you find writing poetry too solitary. You want to create with others – you and others who work for revolution, who believe in ending white supremacy and racial capitalism, will triumph soon.”

Siegel and Wallace both found it essential to communicate the importance of building a village of creatives to their younger selves. Other letter writers also expressed this necessity. Throughout the generations of letters, those who deemed themselves as creators communicated that as much as creators need their peace and serenity to give their whole selves to their creations, they also need time with each other. Many felt that at times they needed others to help them get out of their heads, talk through their process, and become inspired by what others are doing.

Although there seemed to be an emphasis on building and listening to the creative communities, letter writers also noted the balance that must be struck between the communities’ ideas of how creations should be executed and what the writer’s personal opinions and styles preferences are.

This strike of balance can be seen in Rachel Creemers’s, a graduate of 2014, and now a 2D animator, letter to her Div I self. For her Div III Creemers “created a short film based off music from spirited away that was entirely traditionally hand-drawn”

In her letter to her Div I self, Creemers reminds herself that “Your art is soft, melancholy, and pretty, and it just takes time to mature an art style that’s a bit different. It’s not “a dead form of animation” as some of your classmates will tell you throughout the year.” If Creemers took her creative community’s advice, she would most likely have changed how she approached her creative process. However, Creemers decides to stick to her gut and, as a result, “learns more about the world of animation” and “sees so many paths open up before [her]” that she tells herself is “because you cranked on the basics again and again. Take pride in your patience, and the skills you took the time to learn.”

Siegel also learned that she must find a balance between creative collaboration and independent work during her time at Hampshire. Siegel learned this lesson during one of her theater classes. She writes to her younger self, “you have undergone a flattening—and also instructional— experience in your current theater class. For scene study, you built on your Manhattan Project studies, presenting work that was intense, whacky, and both motivated by the script and arguing against its received conventions. In their [Siegel’s creative community] critique, working bit by bit to adjust the exterior details, the class comments advised that you dismantle and deaden every moment until the scene followed the predictable trajectory they expected it to have before your work began. This is a profound turning point for two reasons: First, it is clear that this class will not help you explore work that matters to you. Second, you realize that given that theater is a collective art, continuing in theater means repeatedly confronting this challenge: Just to create the work, you will always have to convince other people to share your universe.”

Like Creemers, Siegel had to learn that sometimes you have to follow your creative gut versus listening to your community’s advice. Siegel also acknowledges in this passage that sometimes that your vision will not always be clear to those around you. There will be times when you are creating, and the community you rely on for guidance will guide you in a direction that does not feel right. In these times, you will have to push for your ideas to be understood and either convince your community to come along for the ride with you or decide to create on your own. Striking a balance between community and independents is one way that letter writers said they could thrive as creators.

2. Self- Forgiveness

It is one thing to create, but it is another to keep creating.

Ask any creator of any medium, and they will tell you this in one way or another. For every ounce of creative juice that we have stored within ourselves, there is an ounce of potential for creators to run into a creative block. When this happens, artists can get down on themselves to question the purpose of their work, the purpose, even, of themselves.

Within the letters, a lot of people wrote to themselves about this notion. They gave their younger selves encouragement to “keep going!”, told themselves, “don’t give up!”, and that it will be “worth it in the end!”.

Nora Hammen, as noted above, a 2021 graduate, currently on her 5th rendition of her book “The Witch University,” summed up the true message behind all these encouragements; she advises herself that “The work you put in doesn’t go to waste just because you don’t use whichever version of it you currently have. You get to learn a lot about writing and creating worlds from that story [the current work a person is producing] alone. You learn that it’s okay to change projects no matter how far along you are with one of them, because it [the essence] will still be there, it will still have an effect on you moving forward. Think about it: what excites you most about your council story world [The book Nora was working on during Div I]? Maybe it’s…the dynamics between the four main characters, or the cultures and governmental structures of the fairies, elves, and mermaids. Guess what, you don’t have to throw those away! I’ve already started brainstorming ways to reuse the magical cultures for a new idea, either including the idea of a council or not, and I might even get to use the same characters! Everything you create has value, even if it never sees the light of day or remains in your head.”

Hammen reminds herself that none of her work is a waste of time. Even if her projects do not come to fruition, the produced concepts can be used for a different rendition of the project or a completely separate idea. And if a complete project is never made, there are still beneficial factors to doing the work, like practice, learning, and inspiration. This is a helpful notion for creators to remember, to help them find the momentum to keep going, to keep creating.

3. Finding art in every day

The last pattern of advice in the letters about being an artist was the idea of being flexible in how you define what it means to live an artistic life. Creemers reveals to her younger self how having a flexible view of how she has made art since leaving college has helped keep up her creative practice. She writes to herself that “It [ her flexible thinking] allows you to be versatile in a market that doesn’t know art. You use your hard-earned skills to teach kids and help them conduct art therapy, you make latte art that makes people smile, you draw your friends’ intimate moments so they can relive happy memories. The problem-solving abilities you cultivate this year help you become a political strategist, as all it really is telling and selling a story, something you absolutely hammered into your brain. The phrase you crystallize of “Think sideways” this year opens up so many job opportunities and even helps you save Hampshire College down the road. You adapt to survive, and when you start thriving, you take the freaking wheel and gun it.”

Creemers studied animation during her time at Hampshire. As she revealed when we sat down to talk about her letter, she was further prepared to head towards a traditional animation studio career. She tells me that she was prepared to be “an artist that is ready to be plugged into an art production line. And that’s all they do. They have made their portfolio incredibly specific to one thing that allows them to be plugged into the art animation machine in particular. And that’s not saying that those artists aren’t spectacular, because there are just so my gosh, so many insane artists who just crank down on one thing. And that can be really valuable. Because you know, then they get really good at character design, or they get really good at backgrounds and stuff like that. But if all you have in your brain is get hired, like do this thing, get hired by big companies profit. There’s a lot that you’re missing out in your own art exploration. Tom [A professor at Hampshire] really grinded this into me at Hampshire. And it was you don’t have to follow the process to a tee. And if you do do that you are more likely to experience artists burnout. And so he forced me… to try out a bunch of new different things” from there, she started to “get out of that artist in a box mindset.”

There are creators who have become before me, there are creators who are working aside me, and there are creators that will come after me. By remembering to work with my community, listen to my creative gut, forgiving myself, and being flexible in my definition of what it means to be an artist, I can count myself as one of them

If you remember all this Reader, you could be a creative too.

Sincerely

Molly Marie

Featured in this letter:

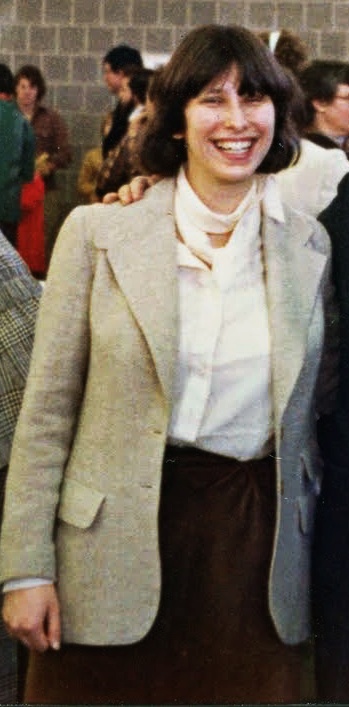

Div III 1978

Div III 1982

Div III 2014

Div III 2021